When Mathematics Meets Reality

A Journey Through Circles, Infinity, and the Nature of Truth

The Impossible Answer

A teacher stands at the blackboard and writes: "What is the circumference of a circle with a diameter of 60 cm?"

The students dutifully calculate:

But one student raises their hand: "I cannot calculate that."

The teacher, puzzled: "Why not? You know the formula."

The student: "A perfect continuous circle? I cannot calculate that—it would require infinite precision. I can only approximate it using a polygon with however many sides you'd like."

The teacher pauses. The room falls silent. Because the student is absolutely correct.

This seemingly simple question—one asked millions of times in classrooms worldwide—contains a paradox that strikes at the heart of how mathematics relates to reality. This is the story of that paradox, discovered through an unexpected journey that began with topology and ended with a question that should trouble anyone who thinks mathematics is "the language of nature."

Part I: The Starting Point—Mathematical Truth as Pattern

Our conversation began far from circles, with a question about mathematical proof and the nature of mathematical objects. Specifically: What did Grigori Perelman actually prove when he solved the Poincaré Conjecture?

The Poincaré Conjecture: A Brief Detour

The Poincaré Conjecture states that any closed, simply-connected 3-manifold is topologically equivalent to a 3-sphere. In simpler terms: if you have a 3-dimensional surface with no holes, and you can shrink any loop on it down to a point, then it's essentially a 3-sphere (the surface of a 4-dimensional ball).

This problem remained unsolved for 100+ years because dimension 3 turned out to be harder than higher dimensions:

- Dimensions 5+: Solved by Smale (1961)

- Dimension 4: Solved by Freedman (1982)

- Dimension 3: Remained impossible until Perelman (2002-2003)

Perelman's approach used Hamilton's Ricci flow—letting manifolds "flow" toward uniform geometry like heat diffusion. The critical obstacle was that singularities form (geometry blows up to infinity). Perelman's breakthrough was classifying all possible 3D singularities and proving they don't accumulate infinitely.

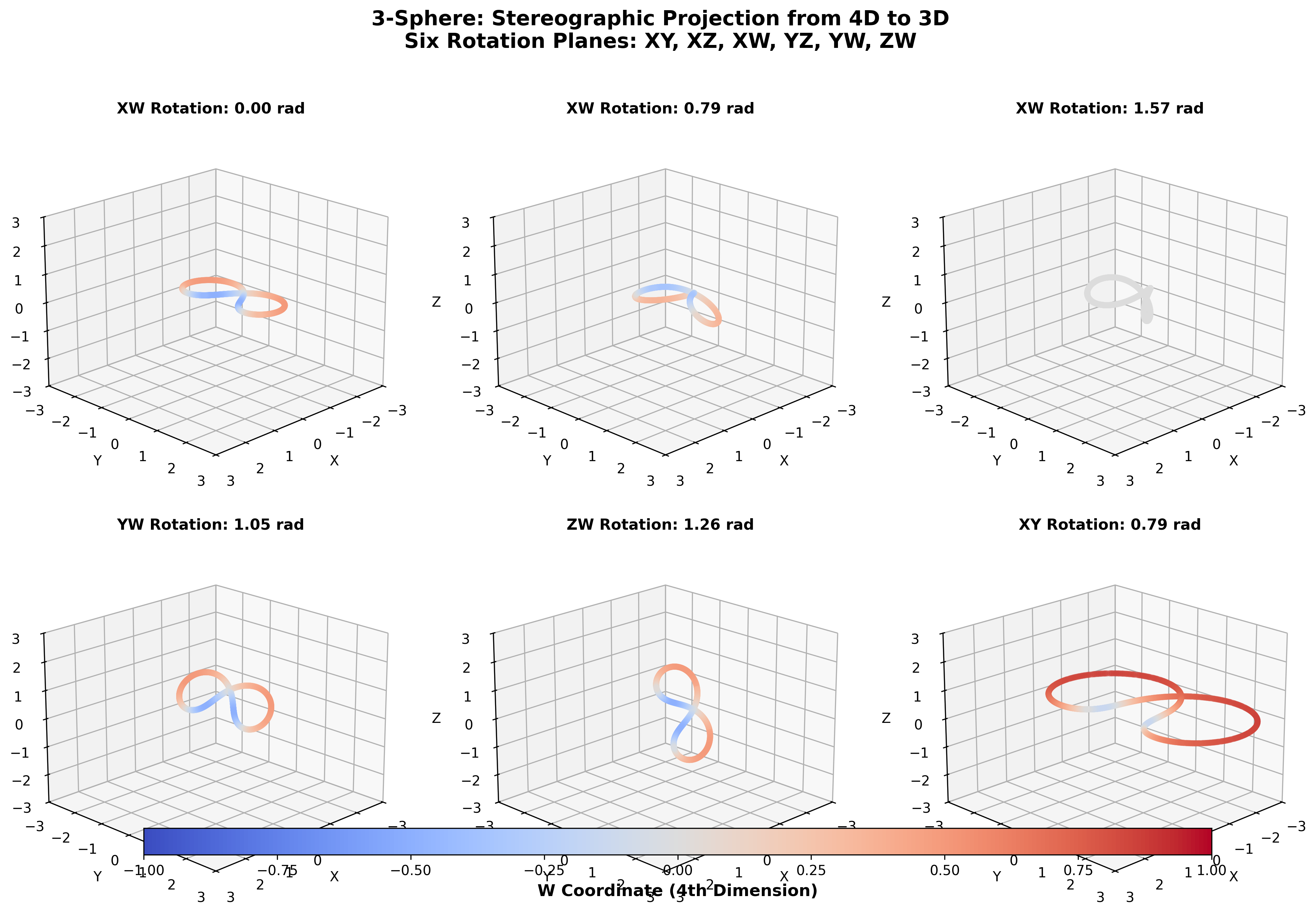

3-sphere rotation visualization showing stereographic projection from 4D to 2D. Points distributed on the 3-sphere surface with color encoding the fourth dimension (blue for negative W-coordinate, orange for positive). Six rotation planes in 4D: XY, XZ, XW, YZ, YW, ZW. This demonstrates that 4D geometry has definite structure when executed—a key point about mathematical objects as generative patterns rather than Platonic forms.

But this led us to a deeper question: What is the nature of mathematical truth itself?

Three Competing Frameworks

We examined three possible answers:

- Platonism: Mathematical objects exist independently, "out there" somewhere, waiting to be discovered

- Formalism: Mathematics is just arbitrary rules and conventions that humans invented

- Something else: ???

The conversation initially leaned toward Platonism. After all, 2+2=4 seems objectively true, independent of human opinion. But then came a challenge:

"It's all made up conventions that people agree on."

Is 2+2=4 really objective? Consider:

- In standard arithmetic: 2+2 = 4

- In Boolean algebra: 1+1 = 1

- In binary: 1+1 = 10

- With synergy/emergence: 2+2 = 5 (two pairs of collaborators become a team of 5 effective units)

All are "true" within their frameworks. None is more "real" than others.

This led to our breakthrough insight:

Mathematical Objects as Generative Patterns

Mathematics is neither discovered (Platonism) nor invented (formalism), but consists of human-created generative patterns with definite computational consequences.

When you implement a mathematical structure computationally, you get constrained outputs. The patterns are human-created; the constraints are real; the outputs are definite but sometimes infinite/incompletable.

Three computational demonstrations we created illustrated this:

1. 3-Sphere Rotation (surface of 4D ball, projected to 2D)

2. Hopf Fibration (circles linking through 4th dimension)

3. AI Attention Flow (model of reasoning dynamics)

All three demonstrated: Human-created patterns → Computational execution → Constrained but non-arbitrary outputs

The visualizations existed as proof: executable code running according to definite rules, producing constrained outputs, possibly describing something real (spacetime topology, gauge theory, AI cognition)—but we cannot prove which.

Technical Detail: The Hopf Fibration Example

The Hopf fibration maps S³ → S² where each point on the 2-sphere corresponds to a circle on the 3-sphere. Remarkably:

- Circles never intersect in 3D

- Yet every circle links with every other exactly once

- The linking happens through the 4th dimension (invisible in 3D)

This is an emergent property: the linking structure is not obvious from the definition. It appears in physics (magnetic monopoles, gauge theories, quantum geometric phase).

When we execute the Hopf fibration computationally with different random seeds, we see:

- Similar clustering patterns (structural consistency)

- Different specific trajectories (variation)

- Constrained but not deterministic behavior

This demonstrates: robust but not rigid generative pattern. The mathematics constrains what's possible without determining exact outcomes.

But this framework raised a troubling question that would become central...

Part II: The Irrational Number Problem

If mathematical objects are generative patterns with definite outputs, what about irrational numbers?

Consider:

These numbers have:

- Infinite decimals

- Non-repeating patterns

- No exact representation

The Perfect Circle Paradox

Take a circle with radius r = 1 meter (exactly).

Question: What is the circumference?

Mathematical answer: (infinite process that never terminates)

Physical answer: Wrap a string around it and measure = finite, complete answer

Which is "real"?

The formula produces an infinite process. The measurement produces a finite result.

But wait—it gets stranger.

The Measurement Illusion

You might think: "Physical measurement is finite, formulas are infinite. Problem solved."

But that's wrong. Physical measurement also never completes.

Measure the string against a ruler:

- First look: 628 cm (close enough!)

- Magnify: Actually 628.3 cm

- More magnification: No wait, 628.31 cm

- More: 628.318 cm

- Electron microscope: Where exactly is the "edge" of the string fiber?

- Atomic force microscope: Where is the boundary between string atoms and air atoms?

- Quantum level: What does "boundary" even mean?

You can always look closer. The measurement never completes either.

So we have:

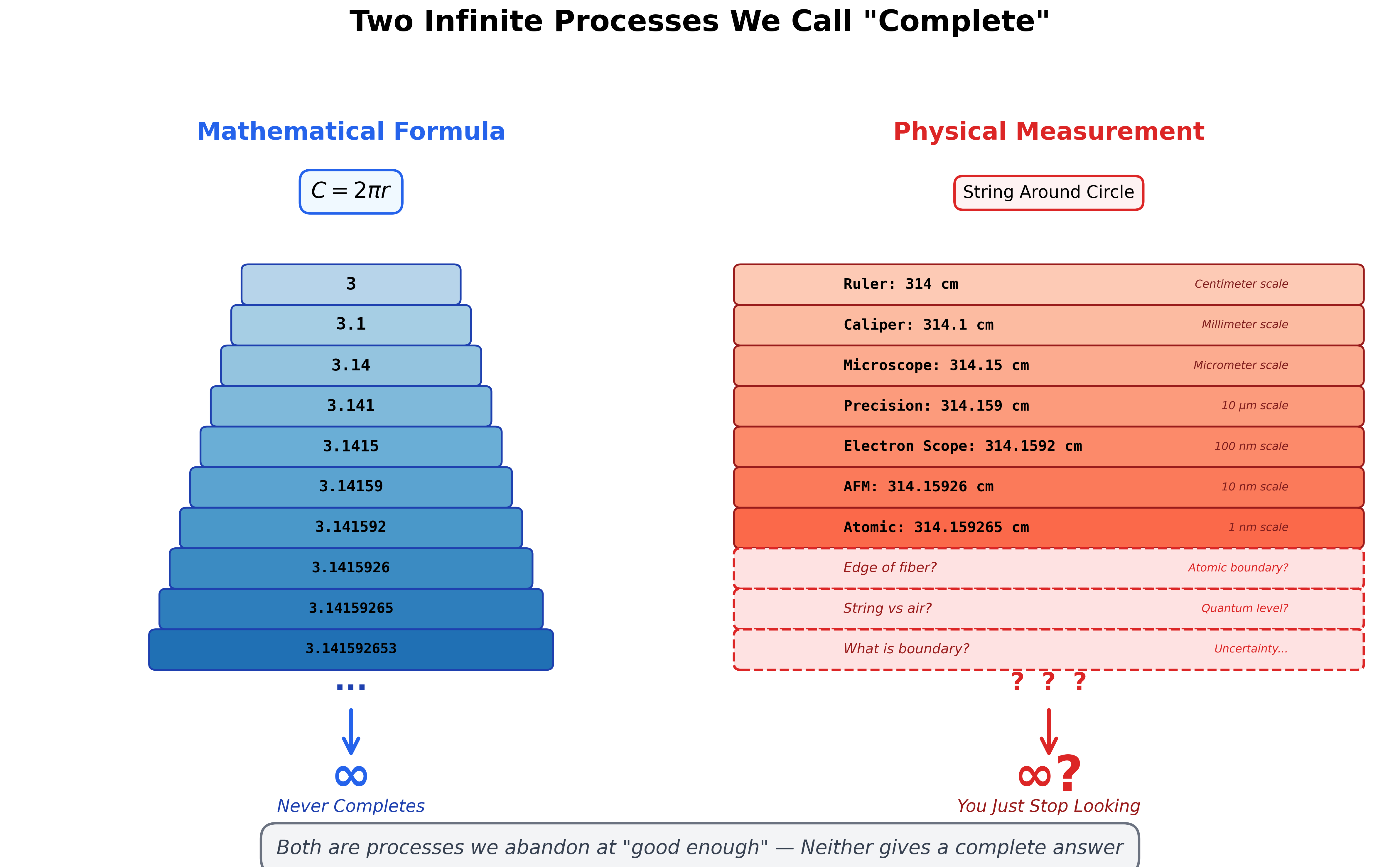

Formula: generates 3.14159265358979... (infinite, never completes)

Measurement: String vs ruler generates 3.14... 3.141... 3.1415... (also never completes—you just stop looking)

Both are processes we abandon at "good enough."

Neither gives a "complete" answer. Both are truncated processes we've declared sufficient.

Two infinite processes side by side: On the left, the mathematical formula continues forever. On the right, physical measurement zooms deeper and deeper—threads become fibers become molecules become atoms... Both never truly complete.

Part III: The Tau Diversion

At this point in our conversation, someone introduced the "Tau Manifesto"—an argument that we should use τ (tau) = 2π = 6.283... instead of π as the circle constant.

The Case for Tau

The argument is elegant:

Circles are defined by their radius (constant distance from center), not diameter. So why is our circle constant the ratio C/D instead of C/r?

Using τ = C/r makes everything cleaner:

- 1/4 circle = τ/4 (not π/2)

- 1/8 circle = τ/8 (not π/4)

- Full circle = τ (not 2π)

Euler's identity becomes:

- ("one turn returns you to unity")

- Instead of ("half turn is negation")

Area formulas gain natural 1/2 factors:

- (just like kinetic energy = (1/2)mv²)

- The 1/2 comes from integration, not arbitrary cancellation

This seems revolutionary!

But Wait

τ doesn't solve our fundamental problem at all.

Both give us infinite decimals:

Same fundamental issue: Formula produces infinite process. Measurement produces finite answer.

τ vs π is just pedagogical preference—which infinite decimal we use. Neither addresses the deeper paradox.

As we realized: "Tau doesn't solve our issues."

Part IV: The Choice of Parameters

This led to a critical insight: Why do we even need π (or τ)?

The Parametrization Choice

We need π/τ because we chose radius/diameter as the fundamental parameter for describing circles.

This choice seemed "natural":

- Circle = constant distance from center (radius)

- Easy to draw with compass

- Conceptually simple

But it's a CHOICE. And choices have consequences.

Alternative parametrizations:

Option 1: Circumference as fundamental

- C = C (given)

- r = C/τ (derived)

- A = C²/4τ (derived)

Option 2: Area as fundamental

- A = A (given)

- r = √(A/λ) (derived, where λ = τ/4)

- C = 2√(Aτ) (derived)

Option 3: Discrete/polygonal

- Define circle as 1-million-sided polygon

- All relationships are rational

- No infinite decimals at all

- "Close enough" to circle for any physical purpose

We picked radius → that choice generated π → π is irrational in continuous math → we now treat this artifact of our parametrization choice as a "deep truth about circles."

But maybe it's just a truth about our framework choice.

Technical Detail: Why Radius Creates Irrationality

When we define circles via radius in Euclidean geometry, we get the equation:

Integrating around this curve to find circumference requires evaluating:

For the unit circle (r=1), this becomes:

The irrationality of π emerges from:

- The continuous framework (real analysis)

- The parametrization choice (radius)

- The integration process

Change any of these, and the "necessity" of π vanishes.

For instance, using a discrete framework (polygons), we get rational approximations that are indistinguishable from π for practical purposes but never require actually computing infinite decimals.

Part V: The Polygon Revelation

This led to the most startling realization of all.

What Are We Actually Computing?

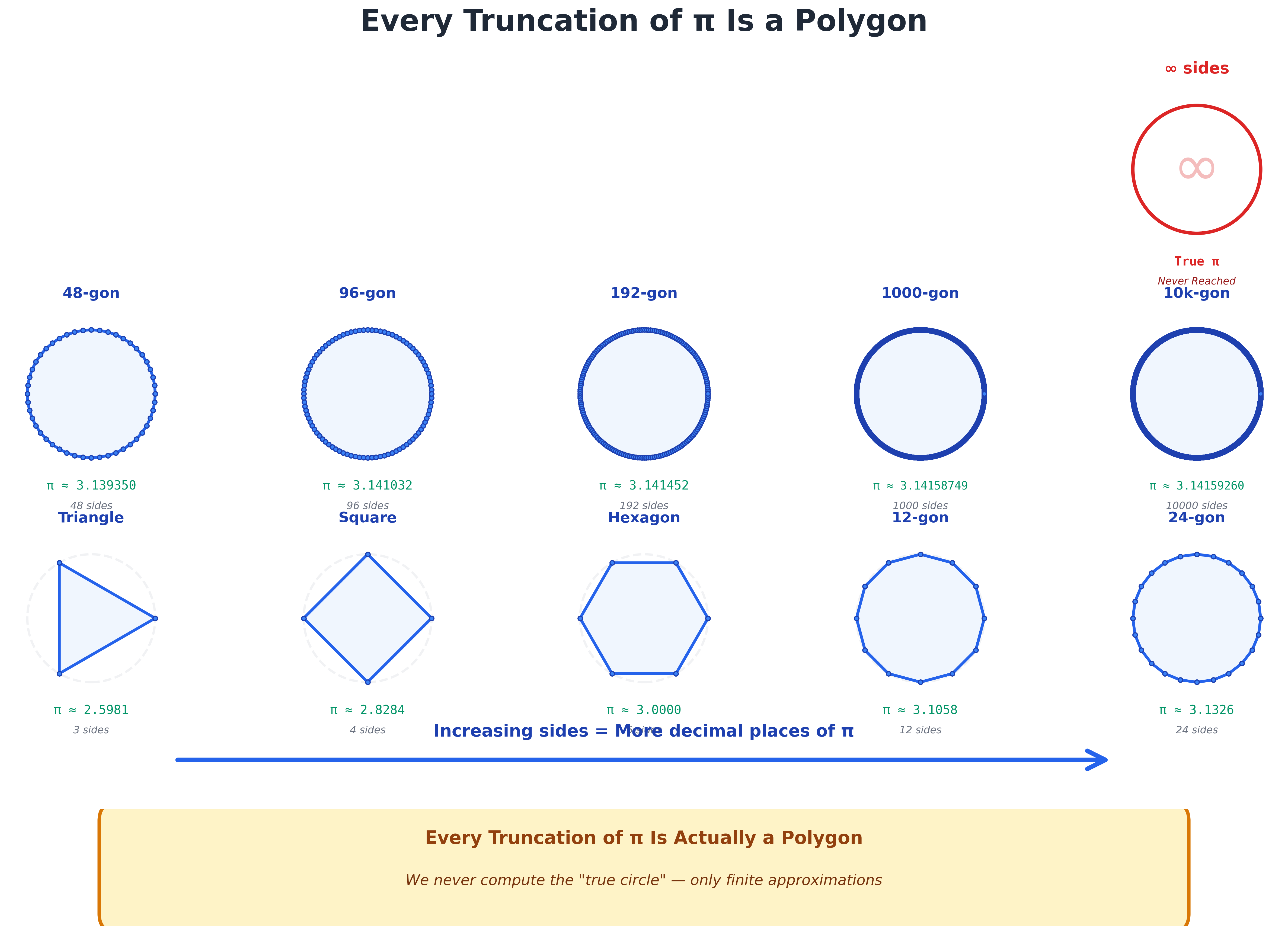

When I use π ≈ 3.14159265... (stopping somewhere), what am I actually calculating?

Answer: A polygon, not a circle.

The polygon-π correspondence:

- π ≈ 3: ~hexagon (6 sides)

- π ≈ 3.14: ~96-sided polygon

- π ≈ 3.14159: ~100,000-sided polygon

- π ≈ 3.14159265358979323846: billions of sides

But it's still a polygon. Still finite. Still discrete.

Interactive: Watch the Polygon Become "Almost" a Circle

💡 Drag the sliders to see how adding sides makes it "look" like a circle. Then zoom in to see the edges are still flat. No matter how many sides—it's never truly continuous.

Progressive sequence showing increasing polygon approximations of a circle. Each step adds more sides, getting "closer" to circularity—but never completing the journey to true continuity.

The Devastating Realization

The "true circle" with "true infinite π" would require:

- Infinite sides

- Infinite precision

- Infinite computation

- Never completable

Since we always truncate π (even at a trillion decimals), we are always doing polygon math, not "true circle" math.

In practice, all mathematics is discrete. We just pretend it's continuous and act like our polygon with 10 billion sides "is basically a circle."

And here's the kicker: For all physical purposes, it is. The billion-sided polygon is indistinguishable from a "true circle" in any experiment.

Continuous Mathematics: An Unreachable Limit

The infinite continuous circle exists only as:

- A limit we approach

- An ideal we never reach

- A process we always abandon

The continuous ideal floats above reality, never touching it. Every actual calculation—whether formula or measurement—is a discrete truncation we've agreed to call "good enough."

Part VI: The Infinite Proof

How do we know π is irrational?

Not From Measurement

No physical measurement has ever detected—or could ever detect—that π is irrational.

Think about it:

- String around a circle: finite measurement

- Most precise instruments: finite measurement

- Any conceivable physical test: finite measurement

If we used π ≈ 3.14159265358979323846... (20 decimals) for every physical calculation ever done, no experiment would detect an error.

From Mathematical Proof

We know π is irrational from:

- Lambert's proof (1768): π is irrational

- Lindemann's proof (1882): π is transcendental

But these proofs assume continuous mathematics.

They prove that within the framework of continuous geometry, π cannot be expressed as a ratio of integers. The integral for circumference, when solved in real analysis, generates an infinite non-repeating decimal.

The infinity of π is a property of our mathematical framework, not a property of physical reality.

Technical Detail: Lambert's Proof Strategy

Lambert proved π irrational by showing that tan(x) can be written as a continued fraction, and that if x is a nonzero rational number, tan(x) must be irrational.

Since tan(π/4) = 1 (rational), and π/4 is therefore irrational, π itself must be irrational.

The proof relies fundamentally on:

- Real analysis (continuous mathematics)

- Properties of infinite series

- Analytic continuation

In a discrete mathematical framework, the proof doesn't apply—because the framework itself is different.

The Framework Dependency

We have:

- Created an idealized mathematical framework (continuous geometry)

- That framework generates infinite processes (irrational numbers) when solving certain problems

- We then treat those infinite processes as "more real" than finite physical measurements

- Even though no physical measurement could distinguish the difference

The string around the circle gives a finite answer. The continuous mathematical ideal generates an infinite process. And we've privileged the framework over the measurement.

Part VII: The Classroom Crisis

Return to our opening scene. The student who said "I cannot calculate that" has revealed something profound.

What We Actually Teach

The lie embedded in mathematics education:

When a student calculates C = 60π ≈ 188.5 cm, we tell them they calculated the circumference of the circle.

But they didn't. They:

- Calculated a polygon approximation

- Truncated an infinite process

- Called it "the answer"

And we all agreed to pretend it was the circle.

The Honest Conversation

Teacher: "What is the circumference of a circle with diameter 60 cm?"

Honest Student: "A perfect continuous circle? I cannot calculate that—it would require infinite precision. But I can approximate it using a polygon with however many sides you'd like."

Honest Teacher: "Correct. We'll use a 100-million-sided polygon, call it π ≈ 3.14159265, and pretend that's the circle. The answer is approximately 188.495559 cm."

What We're Actually Teaching

Not truth. Not reality. We're teaching pragmatic approximation methods while using language that implies exact truth.

We teach children that:

- Mathematics gives exact answers ❌

- π is a number (it's an infinite process) ❌

- Formulas describe reality perfectly ❌

What we're actually teaching:

- Approximation methods that work well enough for engineering ✓

- Symbol manipulation that generates useful predictions ✓

- Framework choices that produce "good enough" results ✓

Part VIII: The Four Options

If circles obviously exist (children can draw them, see them, recognize them), but mathematics cannot exactly describe them... what does that tell us?

Why Does It Work So Well?

If Option 4 is correct, why do our approximations work?

Answer: Polygons with billions of sides ARE indistinguishable from circles for any practical purpose. Our approximations are good enough.

But "good enough" and "true" are different things.

And we teach children—and ourselves—as if they're the same.

Part IX: The Theological Collapse

This brings us to the most profound implication.

The Sacred Claim

"Mathematics is the language of God/Nature/Reality"

- Galileo: "The book of nature is written in mathematics"

- Plato: Mathematical forms are more real than physical objects

- Modern physics: Mathematical elegance indicates truth

What We Discovered

Mathematics is a human-created approximation framework that works "good enough" but fundamentally misaligns with physical reality.

If continuous mathematics can't exactly describe something as simple as a circle's circumference, then:

1. Physics equations aren't "laws of nature"

They're our best approximations using misaligned frameworks

2. "Mathematical elegance" isn't truth

It's aesthetic preference for certain approximation methods

3. Wigner's "unreasonable effectiveness" becomes reasonable

Mathematics works because we keep adjusting it until it predicts well enough, not because it's fundamental

4. Science gives prediction, not understanding

We can calculate what will happen without understanding what's actually happening

What This Explains

- Why quantum mechanics "works" but nobody understands it: We're using wrong framework, getting right-enough predictions

- Why we need renormalization: Infinity signals from framework mismatch

- Why new paradoxes keep appearing: Approximation methods break at edges

- Why physics keeps hitting walls: Continuous math on discrete reality

The Inversion

Old View

"God wrote the universe in mathematics"

New View

"Humans invented mathematics to approximate a universe they don't understand"

The entire Platonic edifice—that mathematical forms are more real than physical reality—inverts.

Physical reality is primary. Mathematics is our tool.

When the tool generates infinities, that's not revealing deep truth—that's the tool breaking because it doesn't match reality.

Part X: The Remaining Mystery

But this creates a new problem.

The Predictive Power Paradox

If mathematics is just "good enough approximation," why does it predict things we didn't know yet?

Examples:

- Maxwell's equations predicted electromagnetic waves before we found them

- General Relativity predicted gravitational lensing before we observed it

- Dirac equation predicted antimatter before we discovered it

- Higgs mechanism predicted Higgs boson decades before detection

How can a misaligned approximation framework predict novel phenomena?

Possible Answers

Answer 1

We got lucky

Unsatisfying. Too many successful predictions for pure luck.

Answer 2

The approximation is so good that it captures essential structure even while missing fundamental nature

Possible. A billion-sided polygon really is almost indistinguishable from a circle.

Answer 3

There's something deeper we're missing

Most honest answer. We don't know.

Answer 4

Mathematics captures pattern even when missing substance

Physical reality has patterns. Mathematics describes patterns. The patterns are real even if our framework for describing them is approximate.

Perhaps this is the resolution: Mathematics captures real patterns using approximate frameworks.

The patterns exist in reality. Our continuous mathematical description is approximate. But the patterns are robust enough that even approximations capture them well enough to predict.

Part XI: Living With Uncertainty

Where does this leave us?

What We Know

- Continuous mathematics cannot exactly describe simple physical objects (like circles)

- All actual computation is discrete (we always truncate infinite processes)

- Physical measurement is also incomplete (you can always look closer)

- Both formula and measurement are "good enough" approximations that we stop at some point

- The choice of mathematical framework determines what "truths" emerge (choosing radius as fundamental creates π)

- Different frameworks are all valid in their domains (Euclidean, Manhattan, discrete/polygon)

- Irrational numbers signal framework mismatch between continuous idealization and discrete reality

What We Don't Know

- Why mathematics predicts novel phenomena if it's just approximation

- Whether physical reality is fundamentally discrete at quantum scales or continues infinitely

- What the "true" description of reality would look like if continuous mathematics is wrong framework

- Whether "perfect" descriptions are possible or if all knowledge is approximate

How To Proceed

In Education

- Teach "good enough approximation" honestly

- Don't claim mathematics gives exact truth

- Acknowledge framework choices and their consequences

- Emphasize that useful ≠ true

In Science

- Maintain epistemic humility about mathematical descriptions

- Treat infinities as error signals, not deep truths

- Explore discrete alternatives to continuous frameworks

- Remember: prediction ≠ understanding

In Philosophy

- Abandon mathematical Platonism

- Accept physical reality as primary

- Treat mathematics as tool, not truth

- Recognize frameworks shape "truths" we find

The Student's Answer Revisited

Teacher: "What is the circumference of a circle with diameter 60 cm?"

Student: "I cannot calculate that exactly. I can approximate it to whatever precision you need. How many decimal places would you like?"

Teacher: "Two decimal places is fine."

Student: "Then C ≈ 188.50 cm. But I want you to know: this is an approximation of a polygon, not an exact circle. The exact answer would require infinite computation, which is impossible."

Teacher: "You're absolutely right. And that's the most important thing you could learn in mathematics."

Conclusion: The Map Is Not The Territory

We set out to understand mathematical truth and ended at a humbling place.

Mathematics is not the language of reality. It is our language about reality. A powerful, useful, predictive language—but still fundamentally human, approximate, and limited.

The perfect circle exists in mathematics as an infinite process we can never complete. The physical circle exists in reality as a discrete object we can measure to some precision.

Neither is "more real." They're different things entirely.

The infinite decimals of π aren't deep cosmic truths. They're artifacts of framework choice—signals that continuous mathematics doesn't perfectly match discrete reality.

When a child says "I cannot calculate the circumference of a circle," they're not confused. They're correct. They've understood something most mathematicians spend lifetimes avoiding:

The map is not the territory.

Mathematics maps reality beautifully, usefully, powerfully. But it's still a map—approximate, incomplete, framework-dependent.

And perhaps that's okay. Perhaps "good enough to predict" is all we need. Perhaps exact truth is neither possible nor necessary.

But we should at least be honest about what we're doing.

We're not revealing eternal truths written in the language of God.

We're creating increasingly sophisticated approximations to a reality we don't fully understand.

And we're doing it extraordinarily well.

But "extraordinarily well" and "perfectly true" are not the same thing.

Never have been. Never will be.

Epilogue: Questions To Sit With

For the reader who has followed this journey to the end, here are questions worth carrying:

If mathematics is approximate, what would "exact" description of reality look like?

Can we develop discrete mathematical frameworks that avoid infinite processes entirely?

Are irrational numbers real, or are they artifacts that signal our frameworks are wrong?

If we can never complete the computation of π, in what sense does π "exist"?

Does physical reality "care" about our mathematical descriptions, or do they merely predict well enough for our purposes?

What other "fundamental truths" of mathematics might be framework artifacts rather than discoveries?

If the perfect circle cannot be calculated, what does it mean to say circles "exist"?

Should we teach mathematics differently, emphasizing approximation over exactness?

Can science give understanding, or only prediction?

What is the relationship between truth and usefulness?

These questions have no final answers. They are invitations to continued thinking.

Because the most important realization from this entire journey is this:

The questions we cannot answer tell us more about reality than the answers we think we know.

References and Further Reading

On Mathematical Philosophy

- Wigner, Eugene. "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences" (1960)

- Hersh, Reuben. "What Is Mathematics, Really?" (1997)

- Lakoff & Núñez. "Where Mathematics Comes From" (2000)

On Continuous vs. Discrete

- Zeilberger, Doron. "Real Analysis is a Degenerate Case of Discrete Analysis" (1991)

- Rota, Gian-Carlo. "Discrete Thoughts" (1986)

On Tau vs. Pi

- Hartl, Michael. "The Tau Manifesto" (2010) - https://tauday.com/tau-manifesto

- Palais, Robert. "π Is Wrong!" (2001)

On the Nature of Proof

- Thurston, William. "On Proof and Progress in Mathematics" (1994)

- Gowers, Timothy. "The Two Cultures of Mathematics" (2000)

On Mathematical Education

- Lockhart, Paul. "A Mathematician's Lament" (2002)

- Devlin, Keith. "The Math Instinct" (2005)